Rebuilt Engines Explained: Process, Suitable Vehicles, and Quality Checks

Outline and Why Engine Rebuilding Matters

– What an engine rebuild involves, from diagnosis to testing

– Which vehicles and use cases tend to benefit most

– Parts typically replaced or reconditioned, plus key quality checks

– Cost, timeline, environmental impact, and risk management

– How to make a confident decision and care for a fresh build

An engine rebuild sits at the intersection of mechanical craftsmanship and practical economics. Instead of replacing an entire vehicle—or gambling on a used engine with an unknown past—rebuilding restores the core hardware you already have to renewed service. For many owners, that means meaningful savings, less waste, and a vehicle that feels familiar yet refreshed. It can also correct chronic issues that crept in over years: low compression from worn rings, unstable oil pressure due to tired bearings, or rough idle from valve wear. When done thoroughly, a rebuild targets root causes rather than masking symptoms.

Why does this path resonate with so many drivers and fleet managers? First, cost control: a properly scoped rebuild often lands below the price of a factory-new replacement and can undercut the total cost of sourcing, shipping, and installing a used unit. Second, predictability: you know exactly which parts and tolerances went into your engine, and you receive documentation to match. Third, resource stewardship: reusing the block, crank, and heads where feasible reduces material demand and the energy footprint associated with manufacturing new assemblies.

Of course, not every failure points toward rebuilding. A cracked block, severely warped head, or catastrophic damage that compromises structural integrity can tip the scales toward replacement. But in the wide middle—high mileage, oil consumption, bearing knock caught early, or a timing failure that bent valves—rebuilding often shines. The goal of this guide is simple: demystify the process, show who benefits, and set clear expectations about parts, measurements, tests, and break‑in. With that map in hand, you can talk confidently with a rebuilder, compare quotes apples to apples, and decide whether a rebuild is the right fit for your situation.

Understanding the Engine Rebuilding Process

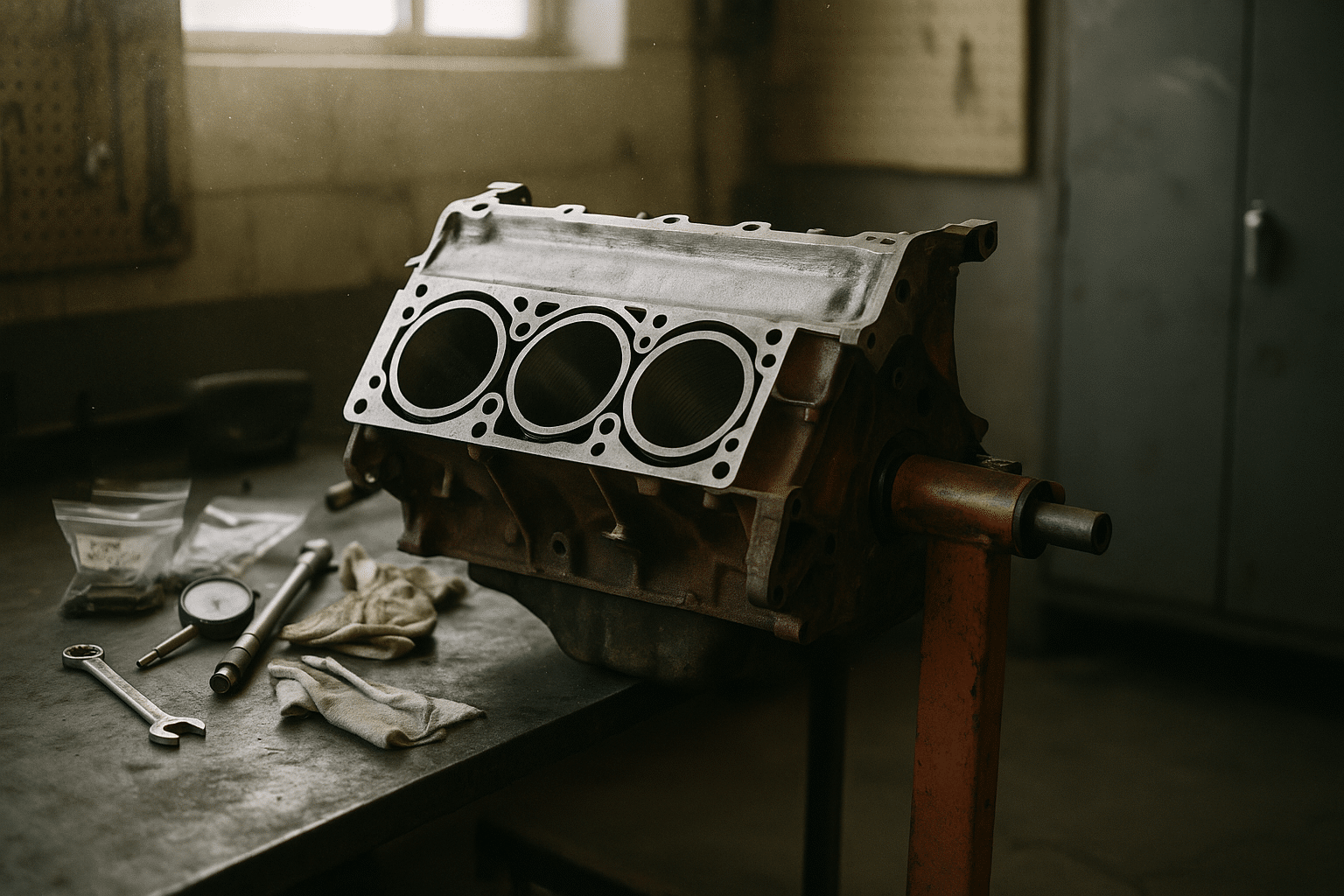

A solid rebuild begins with a disciplined intake. The rebuilder confirms symptoms (noise, smoke, misfires, coolant loss) and reviews maintenance history, then performs baseline checks such as compression and leak‑down tests, oil analysis, and borescope inspection. If the engine is still in the vehicle, these tests help predict what machine work may be needed. Once removed, the engine is fully disassembled and cataloged so every part can be inspected and measured. This “triage” separates components that are reusable after machining from those that must be replaced.

Cleaning and inspection follow. Blocks, heads, and major iron or aluminum parts are cleaned in a hot tank or aqueous cabinet to strip sludge and carbon. Crack detection uses dye penetrant on aluminum and magnetic particle inspection on ferrous parts to reveal hidden defects. Measurements come next: cylinder bores are gauged for taper and out‑of‑round; crank journals are mic’d; main and rod housing bores are checked; deck and head surfaces are measured for flatness. Clearances are typically controlled to thousandths of an inch, and a documentation sheet records target and actual values.

Machining restores geometry and surfaces. Common operations include boring and honing cylinders to a new oversize with a plateau crosshatch (often around a 40–60 degree pattern), line‑honing main bores, resurfacing decks and heads to achieve proper gasket sealing, reconditioning valve seats and guides, and polishing or grinding crank journals as needed. Balance work reduces vibration by matching piston and rod weights and fine‑tuning the rotating assembly, often to within a couple grams. The aim is repeatable oil film stability, ring seal, and heat transfer.

Assembly is methodical and clean. After final washing to remove abrasive residue, the rebuilder installs cam bearings, freeze plugs, and oil gallery plugs, then fits crankshaft and bearings while verifying oil clearance with precision tools. Pistons receive new rings with end gaps set to application needs (street builds commonly use a modest gap factor per inch of bore), and ring orientation is staggered. Fasteners are torqued in sequence using angle or stretch methods where specified. Sealants are applied sparingly to critical joints, and timing components are aligned to factory marks.

Testing validates the work. Cylinder heads are pressure‑tested for leaks, short blocks are primed for oil pressure, and complete engines may see a run‑stand test. Post‑assembly metrics often include: initial oil pressure at idle and specified rpm, compression numbers per cylinder, and leak‑down percentages (single‑digit readings are typical for a fresh build). The engine ships with a break‑in plan—varied rpm, no prolonged idling, and an early oil and filter change—to protect new surfaces while they mate. In short, the process is a structured journey from evidence to precision, with measurements and cleanliness as the guiding stars.

Which Vehicles Benefit from Rebuilt Engines?

While nearly any worn engine can be rebuilt, certain vehicles and use cases gain outsized value. High‑mileage daily drivers with solid bodies and frames are prime candidates: if rust is minimal and the transmission, brakes, and suspension are healthy, a rebuild can add years of dependable service. The math often works like this: rebuilding falls in a mid‑four‑figure range for common engines, whereas replacing the entire car introduces taxes, title fees, and higher insurance premiums—costs that rarely show up on a quick comparison but matter in the long run.

Fleets and work vehicles benefit from predictability. A van or light truck that idles frequently, tows, or carries heavy loads may wear rings, bearings, and valve guides before the rest of the chassis shows age. Rebuilding scheduled around downtime can return that vehicle to service without the uncertainty of a used engine’s history. Documentation of clearances, machining, and parts used helps fleet managers track reliability and plan oil and filter intervals. In many cases, this approach reduces total cost of ownership compared to rolling the dice on a salvage unit.

Enthusiasts and owners of older or low‑production vehicles often see rebuilding as the practical path. New replacement engines may be scarce, expensive, or simply unavailable. A rebuild preserves original castings—block, heads, sometimes even matching‑number components—while bringing tolerances back within specification. For restoration projects, that authenticity matters. For specialty off‑road or marine applications, tailoring clearances and materials to duty cycles (extended high load, frequent temperature swings) can outperform a generic replacement tuned for average use.

There are also situations where rebuilding is less attractive. If the block is cracked, head bolt threads are badly torn, or an overheat has annealed aluminum past recovery, machining may not restore integrity. Severe lubricant starvation that welded bearing material to journals can require a new crank and connecting rods, shifting costs upward. Availability of parts plays a role too; if critical components have long lead times, a quality used or remanufactured unit might return the vehicle to the road sooner.

How do you decide? Consider these signals:

– The chassis is solid and other major systems test well

– The failure mode is contained (e.g., worn rings, bearing wear, valve leakage)

– Parts availability is good and machining options exist locally

– You value documentation and known tolerances over unknown history

Balanced against labor and downtime, rebuilt engines tend to reward vehicles with stable ownership plans—drivers who intend to keep the car, fleets that manage assets by the numbers, and enthusiasts restoring a machine that still has plenty to give.

Parts and Quality Checks: What to Expect

A thorough rebuild is defined as much by what gets replaced as by what gets measured. Many components are renewed by default because their wear patterns are predictable and the cost is modest relative to labor. Expect a comprehensive gasket and seal set, main and rod bearings, piston rings, and a new oil pump or a meticulously inspected and clearanced pump. Timing components—chain or belt, guides, tensioners—are typically replaced, along with cam bearings and core plugs. In the valve train, fresh valve stem seals and reconditioned or replaced valve guides are common, and valve seats are cut for proper sealing. If spring pressures are out of spec, new springs may be specified to protect cams and lifters.

On the rotating assembly, the crankshaft is measured for straightness and journal size; polishing or grinding to an undersize with matching bearings restores geometry. Connecting rods are checked for big‑end roundness and small‑end bushing wear; resizing ensures uniform clamping. Pistons are inspected for skirt wear and ring land condition; depending on bore size after machining, new pistons may be chosen to match an oversize. Balance work aims to minimize vibration and bearing loads by matching component weights and refining the crank’s counterweights.

Quality control is both discrete and holistic. Discrete checks verify individual dimensions:

– Cylinder bore diameter, taper, and out‑of‑round after honing

– Main and rod bearing clearances, often in the 0.001–0.003 inch range for many street applications

– Deck and head flatness to ensure gasket sealing

– Valve guide clearance and seat concentricity

Holistic checks consider system behavior:

– Oil pressure during priming and initial run‑in

– Cylinder leak‑down percentages, with low, even readings across cylinders

– Coolant system pressure testing to confirm sealing under heat

– Noise and vibration levels at idle and varied rpm

Cleanliness is a hidden but decisive factor. After machining, abrasive residue can linger in oil galleries and ring lands. Effective shops wash parts multiple times and use brushes to chase galleries, then assemble in a clean area with lint‑free materials. You should expect to receive tangible proof of quality: a measurement sheet listing clearances and surface work, torque logs or checklists, and break‑in instructions specifying oil type, rpm variation, and the timing of the first fluid change. Some builders include photos of critical steps, such as bearing shell stamps or crosshatch patterns, to document the work.

Finally, realistic expectations. A rebuilt engine targets factory‑like reliability and efficiency, not a dramatic power surge, unless performance parts and calibrations are explicitly part of the plan. With proper installation, careful break‑in, and timely oil and filter service, owners often see service life comparable to a new unit. The combination of fresh wear parts, corrected geometry, and verified clearances is what earns long‑term confidence.

Costs, Timelines, and Risk Management

Budgeting for a rebuild means more than a single number. Costs vary with cylinder count, accessibility, parts selection, and the extent of machining. For many mainstream engines, a full rebuild commonly falls into a mid‑four‑figure range including parts, machining, and assembly, while labor to remove and reinstall the engine can add significantly depending on the vehicle. Specialty or high‑output platforms may push upward due to forged components, extensive head work, or scarce parts. Compare that to a used engine: the sticker price might look lower, but you assume unknown wear, potential internal damage, and limited warranty duration.

Timeline is driven by machine shop workload and parts availability. A straightforward rebuild with readily available components can take roughly one to two weeks of shop time once teardown begins. Add days for shipping if rare components are needed or if the block requires specialized processes. Good communication helps: a clear estimate that lists machining steps, parts, and target dates reduces surprises. If your vehicle is mission‑critical, ask about scheduling the job around parts arrival so downtime is minimized.

Risk management starts with diagnosis. Identify the root cause—overheating, lubrication failure, detonation—so it can be fixed in the rebuild and in the vehicle systems that support it. Replace or inspect the cooling system, filters, sensors, and fuel delivery to avoid repeating the failure. On the engine itself, insist on measurement records; these documents are your audit trail and a powerful tool if issues arise later. Consider the coverage terms offered: some builders provide written coverage on workmanship for a defined period or mileage, often contingent on documented maintenance and proper installation.

Practical comparison points include:

– Scope of machine work listed line by line

– Parts described by specification level (meeting original equipment standards or performance‑rated)

– Measurement targets and actual values shown

– Break‑in procedure provided in writing

– Post‑install checks, such as initial oil pressure and temperature monitoring

From a long‑term view, the value equation favors transparency. A slightly higher upfront price that includes precise machining, new wear parts, and testing can save money over time by avoiding repeat labor. For daily drivers and fleets, that predictability translates to fewer breakdowns and more efficient maintenance cycles. For enthusiasts, it protects the investment of time and care poured into a project. Put simply, clarity today prevents costly mysteries tomorrow.

Conclusion: A Practical Path to Renewed Reliability

Choosing a rebuilt engine is a decision to invest in known quality rather than gamble on unknown history. The process is systematic: inspect, measure, machine, assemble, and verify. Each phase has a purpose tied to physics—restoring oil film support with correct clearances, regaining compression through precise ring seal, and ensuring thermal stability via flat, clean mating surfaces. When these fundamentals are handled with care, the result is an engine that starts easily, idles cleanly, and withstands daily demands without drama.

If you are weighing options, use a structured checklist:

– Confirm the vehicle merits the investment (solid chassis, good transmission, manageable rust)

– Pin down the failure mode so root causes are addressed

– Review a written plan listing all machining operations and replacement parts

– Ask for target clearances and actual measurements

– Get the break‑in plan and coverage terms in writing

Plan for installation and early maintenance. Fresh engines benefit from careful break‑in: varied rpm, moderate throttle, and no extended idling during the first few hundred miles. An early oil and filter change helps remove initial wear particles and assembly residue. Monitor oil pressure, coolant temperature, and any unusual noises. If something feels off, stop and call the builder; early intervention is far easier than correcting compounded issues later.

For daily commuters, a rebuild can postpone an expensive vehicle replacement and stabilize monthly costs. For fleets, it supports uptime targets and predictable budgeting. For restorers, it preserves original components while restoring capability. Across all cases, documentation is your ally; it turns a complex craft into a transparent service with measurable outcomes. With clear expectations, careful shop selection, and disciplined maintenance, a rebuilt engine can offer a long, steady second chapter—one that rewards patience, precision, and practical thinking.